Archive for the ‘necropolis’ Category

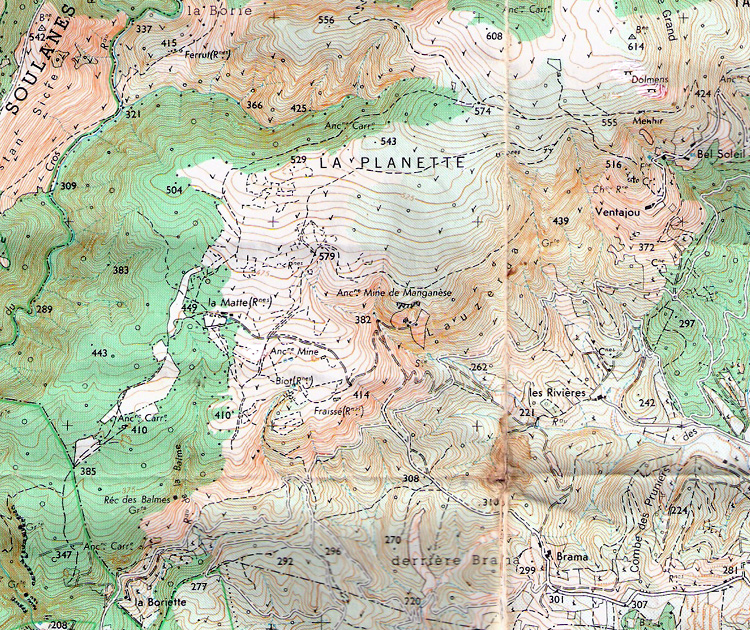

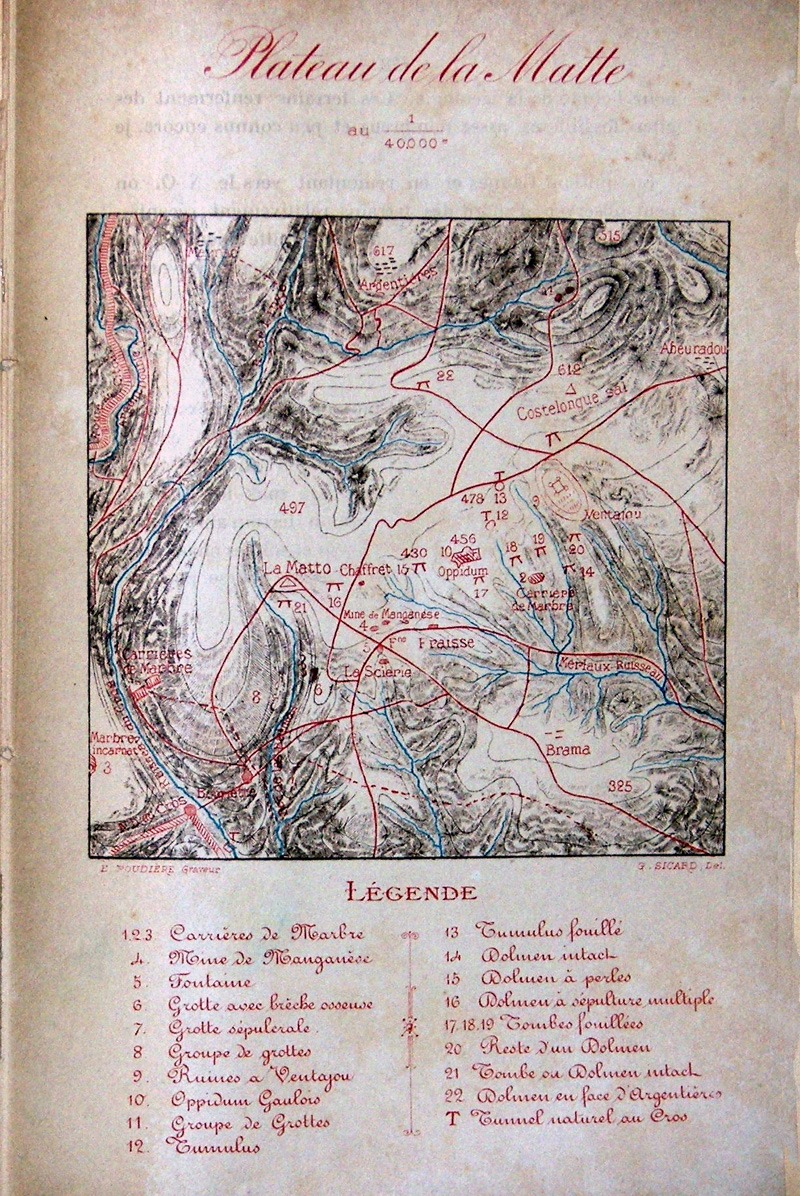

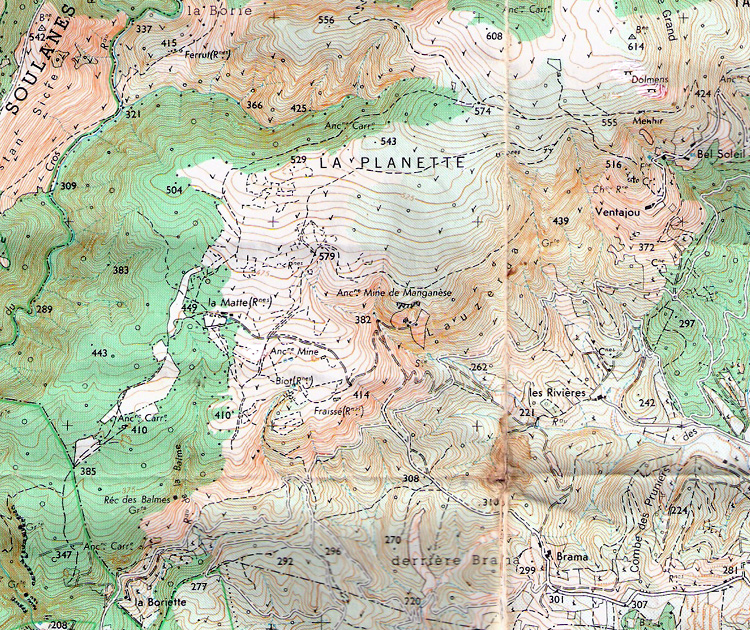

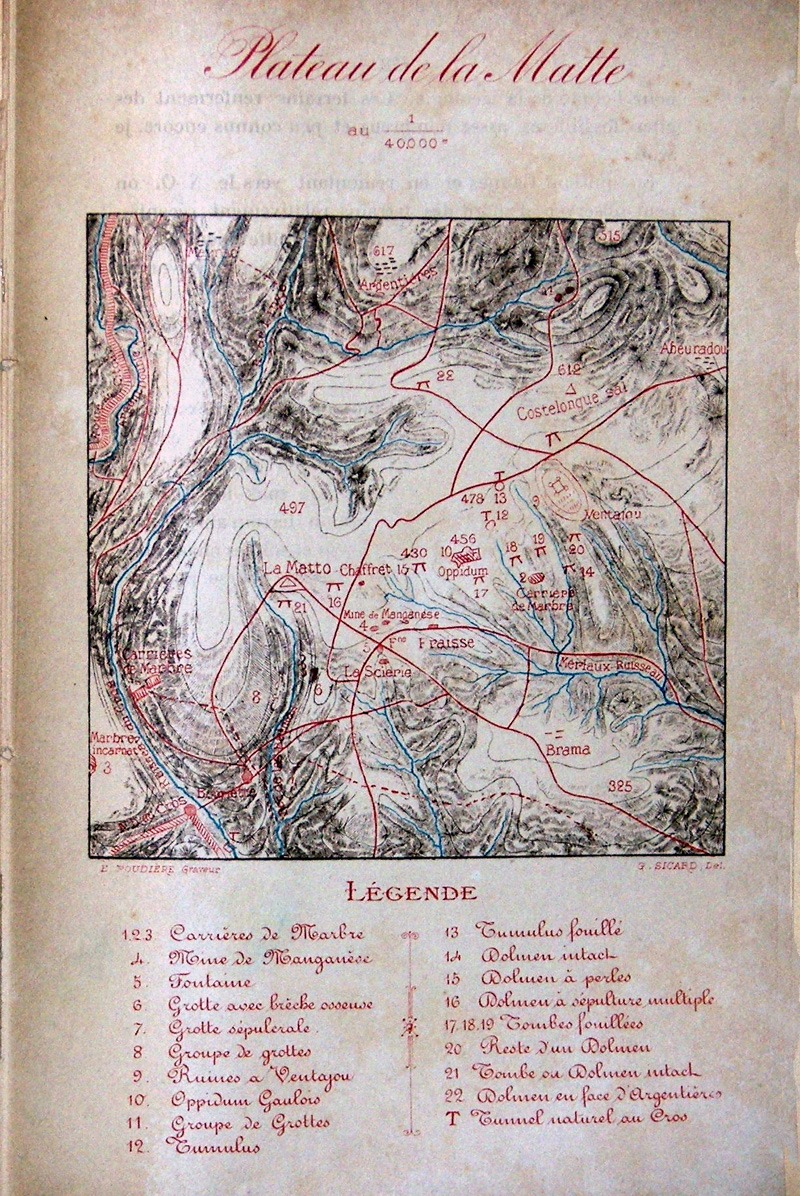

The archaeological story of the dolmens of La Matte (or la Planette – or Planete, the official ‘lieu-dit‘ as it appears on the land-register) begins with Germain Sicard’s report and map of his visit in 1891. Two years later Jean Miquel, of Barroubio, also explored the plateau and found one more dolmen that Sicard had missed.

The story ends in the late 1952, when le docteur Jean Arnal published his collected reports : ‘Excursions sur les Causses de Minerve’. Here he recounts how, during the summer of 1947 (World War 2 barely finished) he covered 250 kilometres by car across all the limestone uplands around Minerve. He explored le Causse de Siran, or St. Julien, the causses de Minerve, les dolmens des Lacs and the nécropolis de Bois-Bas.

For the 7 kilometre walk around the plateau de la Matte, he had as guides a father-and-son team of truffle-hunters, MMrs. Agussol. As expert companions he brought Odette and Jean Taffanel, and Madeleine Cavalier and Louis Jeanjean. The Taffanels – a brilliant autodidact brother and sister team – had made their name locally and nationally by discovering a Neolithic/Bronze age/Iron age complex above their village of Mailhac.

Together they brought the total of tombs to 16. It was an impressive achievement – marred only by the lack of a detailed map, or any coordinates. His textual descriptions seem accurate – until one tries to follow them. An initial gross error occurs when he lists his discoveries : ‘en allant d’est en ouest’ – when in fact he means the opposite: from west to east.

His naming is also less than helpful: his two ‘dolmens de l’Oppidum’ are nowhere near the so-called ‘oppidum’ – they are half a kilometre to the south-east, above the ancient manganese mine. Other names for dolmens seem picked from a hat: ‘le dolmen de la vallée du Cros’ is high up on the top of the plateau and over half a kilometre south-east of the valley and the Cros stream.

Arnal’s report is at pains to accord earlier researchers due respect, while asserting the progress that archaeological studies have achieved – and bemoaning the damage done to the historical record by the incompetencies of others. He remarks on the accelerated damage in the intervening decades: heedless treasure-hunters are castigated, and one local man is named : ‘un docteur Delmas, de Rieux, aurait vidé quelques sepulchres’. A veritable grave-robber! He later describes the situation thus: ‘la destruction sur le plateau de la Matte a été accélérée au début de notre sciècle par des fouilles intempestives pratiquées par des collectionneurs qui sacrifiaient l’architecture à la recherche de belles pièces’.

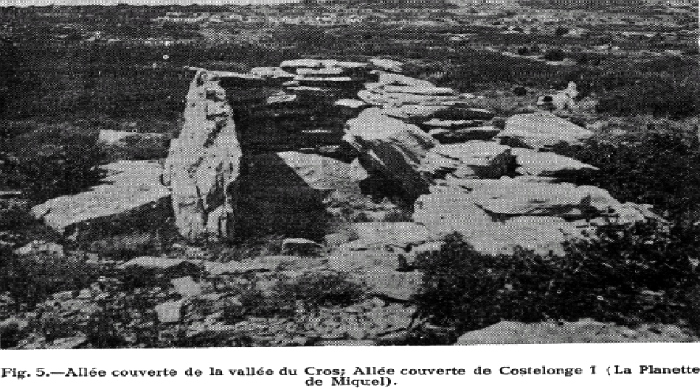

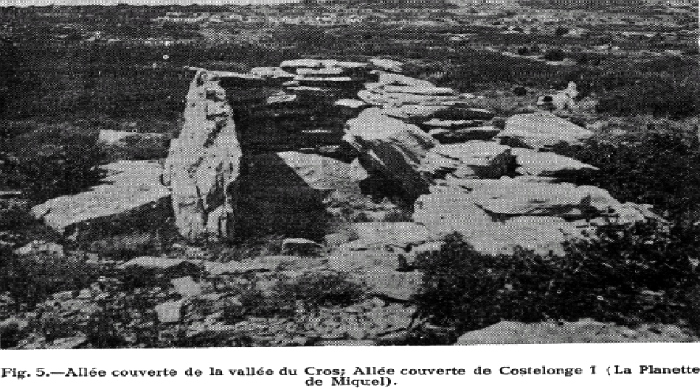

Jean Arnal is held in the highest respect for his work in the region – but his exemplary character is not mirrored in his style of writing. It is already heading in the direction of ‘scientist-speak’. To convey the impact of this extraordinary place, he falls back on the words of Germain Sicard, written 60 years before : ” C’est un vaste champ de calcaire bouleversé, un chaos en miniature, une ancienne plateforme brisée par quelque convulsion du sol…”

His photos however, do manage (despite the poor reproduction) to convey its earlier state of barren abandonment – and its flatness: it is indeed a planeto.

This view of Costelonge 1 extends for many hundreds of metres – before dropping away abruptly – there is nothing growing taller than knee-high. Nowadays evergreen oak and box and scrub-pine crowd the scene – the sheep and goats and wood-gatherers are all long gone. The archaeologists too seem to have lost interest in the place and would seem content to let it all fall from memory. Their work and their careers were funded by taxpayers’ money, but they none of them seem to consider that they owe anything much back to us, in the way of information, explanation – or even simple direction. Did they not think that we too would want to know more about our ancestors – and perhaps visit their extraordinary tombs?

Were it not for researchers like Bruno Marc, and Joel ‘un modeste chercheur‘, and myself – this extraordinary place would disappear completely from public conciousness, overwhelmed by undergrowth and ignorance.

My own account and photos of these dolmens will appear, over the following weeks, in their own Pages.

Childhood interests can ignite life-long passions. For Jean Miquel de Barroubio, in the 1860’s, his long walk to and from school began a distinguished career as collector and researcher of the complex geology of our region. For Germain Sicard, at the same time, the hill above his family ‘domaine’ at Les Rivières, Félines-Minervois, must have been a similar playground, full of archaeologic wonders.

From the Bronze age hillfort of Le Cros at the western end, to the mediaeval castle of Ventajou at the east, the plateau of La Planette – which extends over an area of 400 hectares (3 km long by 1 km wide) – is filled with fascinating stone structures : 16 megalithic tombs, two burial mounds, ancient mines, marble quarries, a stone fort and a standing stone. It is also called La Matte, after an impressively restored farm on its southern lip.

Sicard reported on his finds, in a bulletin of S.E.S.A. in 1896. He had gone up there in 1891 with his good friend Capitaine Savin, who was more interested in the ‘étrange construction’ in the middle of the plateau:

Guy Rancoule, senior departmental archaeologist specialising in the Iron age, confirmed to me recently that this was indeed a military stronghold – but of much later construction. It’s strange – but it’s not an oppidum.

In the same bulletin, Sicard published his map of this extraordinary place:

It was this map, plus the report written by le Docteur Arnal in 1948 ‘Excursion sur les causses de Minerve’ that has lead me a merry chase. Over many visits I have only managed to find two of the dolmens, the one menhir, and the ‘oppidum’.

Bruno Marc has done much better: he found most of them back in 1996. Recently he has included a few scanned photos of some of them, on his site.

But then a week ago – out of the blue – I received a comment here on this site, and then detailed emails from another dolmen-hunter: Joel. And it was Joel and his precise GPS coordiates that enabled me to visit six dolmens up there, this last weekend – all in one day. I appreciate how many hours and days of laborious searching were needed. Joel’s discovery of these previously imprecisely-located sites has impressed me immensely – and when you go up there you too will realise how difficult it is to find anything in this extraordinarily-jumbled landscape.

Equally chaotic is the naming and numbering of each tomb. Sicard, Miquel, Arnal and Bruno have all given different names to the scattered dolmens. With GPS and by working strictly from West to East I am proposing a definitive placement that will be presented to la Société d’ Etudes Scientifiques de l’ Aude, as part of the first complete geolocalised Inventory of the megaliths of the Aude.

Over the next few weeks, each of the six dolmens I visited will be given their individual Page. And in the meantime, I might just get back up there to find all the others.

Vodpod videos no longer available.

It’s July Friday 28th. 1922, the second day of Germain Sicard & Philippe Hélèna’s visit to Camps-sur-l’Agly. Germain is 71 and a founder-member of France’s oldest natural history society, SESA ( and twice its president), and young Philippe will soon inaugurate Narbonne’s Musée de Préhistoire. This afternoon Marie Landriq and her husband, Octave, the village school-teachers, plan to take them to see a ‘dolmen’ that they had discovered the year before, near the village, close to the top of a massive rock outcrop called le Roc d’en Mourges. Eighty-odd years later I am following in their footsteps – but it is not made easy : there is no Roc d’en Morgues on the map. It may be le Roc d’en Benoit. In old Languedocienne, both Mourges and Benoit signify a monk. I am not convinced that it is anything more than an accidental rock-formation.

Les Landriq found calcinated bones and blackish or blackened (noiratre) pottery shards close-by. This may well have served as a funerary site in some distant past – but its very situation on a steep slope, plus the absence of real orthostats, and the lack of any dateable grave-goods – all should have insisted to Sicard, that this was not a dolmen at all.

But these were early days for archaeology – and besides, Sicard was a guest of Les Landriq – and Marie Landriq may possibly have been ‘a formidable woman’ – such that the 71 year-old doctor found difficult to contradict. On the subject of questionable rock-carvings and ‘cupules‘ Sicard apparently has his critics: Yves Le Pestipon of L’Astrée website is one –

‘Rares sont ceux qui croient en Germain Sicard. Des archéologues bien connus le traitent d’affabulateur.’ [that he makes up stories . . .]

Yves is a prolific writer and researcher of dolmens and rock-carvings : here, he is bemoaning the fact that Sicard might have misled him concerning some ‘cupules’ in a rock. He finally finds them – and finishes by celebrating Sicard’s accuracy on this occasion- ‘Germain Sicard n’est pas un affabulateur !’

In the course of my travels in the wheel-ruts of Sicard and Co. this summer, my doubts about Marie Landriq’s finds have been replaced by admiration and amazement. Her zeal and dedication resulted in a handful of significant discoveries : her own Page will appear soon.

Les Landriq have a few more neolithic discoveries to show the experts from Carcassonne, and after a day of rest, it’s just Octave and Germain who mount their bicycles and head east through Cubières and Soulatge, to reach Ruffiac. On the way they pause at Paza where the owner of the domaine tells them blithely that he recently knocked down a dolmen at Coumezeil, a farm close-by. M. Guizard nous parle encore d’un autre dolmen, que lui-même aurait détruit récemment près de la bergerie de Counezeil, au nord de Paza, un peu à l’ouest de la côte 411.

Sicard did not go to examine it. This could possibly be the dolmen referred to in Michael Hoskins’ Corpus Mensurarum, as Paza 1. Nor is the picture clarified by J-P Bocquenet, who – in his doctoral thesis of 1994 (supervised by Jean Guilaine) – writes about La nécropole de Paza :

Trois dolmens et un petit site d’habitat constituent cette nécropole. Certains auteurs citent un cromlech qui serait en fait un dolmen ruiné ou un menhir. Les structures mégalithiques se trouvent sur la pente sud de la colline qui domine la bergerie de Paza.

This is confusing on a number of accounts: there is indeed a menhir in the vicinity – and it is most definitely not a ruined dolmen but stands within a distinct cromlech of stones : I visited it during this trip. It has recently been waymarked – by a local man, Jean-Jacques Pannolié, who is acknowledged as an expert in these matters – as a cromlech, and I have unearthed Mme. Landriq’s notification of it to the Société Préhistorique Francaise, in June 1924. My photos of it appear on the Coumezeil menhir and cromlech Page, to the right.

So it would appear that Boquenet was blindly citing other authors and did not visit any of these sites. There is no necropolis at or near Paza, or Coumezeil, for that matter. A necropolis must consist of more than two tombs – let’s say ‘within a stone’s-throw’ of eachother. The menhir and cromlech are about 800 metres from Paza, and 500 from Coumezeil. No one has yet provided any precise locations for Paza 1 dolmen, or II, or III. There is another menhir at Trébals, but that is 2.5 km. from Paza. And there is another dolmen, at La Roudouniero (found by Marie Landriq a year later : Bulletin de la Société préhistorique française 1923). It stands 900 m. south of Paza – yet has been called Paza III.

Let us leave the confusion at Paza behind – as did our pair of dolmen-hunters. They have another 8 kilometers on their ‘machines’ ‘ under the fierce rays of the sun, along stoney roads – before they reach la métairie de Triolles – or Trillol as my map has it. They leave their ‘bécanes’ there and set off on foot for the last climb, with their knapsacks of ‘vittals’. The 71-year-old Germain must by now have been feeling his age, for he settles down in some shade while Octave disappears into the undergrowth.

Sooner, probably, than he wanted he gets a call – and it’s off again up the slope. A short scramble later Sicard finds himself ‘en face d’un beau dolmen, bien entier, qui se dresse majestueusement . . .’

And it is a surprise, and a remarkable sight, after all the sad little ruined and degraded tombs scattered over the hills of les Corbières and le Minervois. It’s a complete and rather impressive ‘dolmen simple’.

It is worthy of inclusion in any guide-book, but it does not appear in any report or guidebook, or on any map. How regional historians have missed this – is yet again beyond my comprehension. A local team have done good work in clearing and waymarking the track – but have not yet alerted the wider public to this impressive megalith.

Sicard quickly realises that it has been ransacked – and has a culprit ready to hand : ‘l’agent-voyer, qui surveillait l’exécution de la route de Montgaillard, M. Isidore Gabelle, collectionneur érudit et acharné’.

It was, he suspects (and with absolutely no proof) the Superintendant of Roads, who is a learnéd and voracious collector. But they get over this bitter moment and decide that, given the beating sun, they should enjoy the shade offered by the dolmen – and have their picnic there, under its table.

I too settled in, set out my solitary snack, and thought of them. Trois hommes dans un dolmen (sans parler du chien).

It was a fine end to Sicard’s second visit – but there was a long bicycle ride ahead. For Octave it was the 20 km. ride home to Camps – but for Sicard it was 30 kms. down through Les Gorges de Galamus to the station at St. Paul-de-Fenouillet, and the long journey back to Carcassonne.

I now have photocopies of Jacques Lauriol & Jean Guilaine’s 1964/65 dig, and some time to compare their diagrams with Paul Ambert’s. It’s worth noting that in the five years combined, only three photos can be accessed – and only then with some difficulty. And that Lauriol had to rely on a M. Gibert of Lauragel for the photo of dolmen no. 2 (Lauriol’s numbering, which jumps around without reference to any north-to-south progression.)

What kind of science were they all practicing, if photography was so absent? What was their idea of a record of events, of architecture? ( To be accurate, Auriol or was it Guilaine, does actually mention the word ‘architecture’ – it’s a rare occurence. It might be why Jean Guilaine has become one of France’s foremost writers on the prehistoric world of southern Europe – he seems to have a wider perspective over the entire prehistoric period in France . He’s also written one of the very few ‘prehistoric novels’ : ‘ Pourquoi j’ai construit une maison carrée‘. EPONA, Paris (1994)

The situation up there on the Causse seems to get more confused with every team that visits. Both of these teams – the last serious excavations, now 40 years ago – refer to all the many previous researchers in a generalised and dismissive way. And of course they never fail to take a swipe at ‘les fouilleurs clandestins’ , as if 4000 years of labour and occupation ( which is 120 generations of shepherds and farmers and hunters and plain simple poor folk ) wouldn’t have had some effect on the tombs . . .

But there seems to be little readiness to establish any sensible order in the numbering or location of the dolmens. There seems to be little serious acknowledgement of previous work – let alone a concerted effort towards building a picture of the prehistoric life that would be accessible to the general public. The overall impression I get is that of a closed group of researchers in competition with themselves. The blanket laissez-passer is ‘Le Patrimoine’ – they are doing it for the common good, for the history of us all. And beneath this shroud all manner of confusion and misinformation is allowed to proliferate.

While trying to locate the last three dolmens of Les Lacs, I came upon this structure.

In my eagerness to locate dolmen number 4, I thought it was this. But now that I’ve had time to look at my photocopies of Lauriol & Guilaine’s drawings and diagrams, I realise it’s something else entirely. In the heat of the moment I convinced myself that it shared similaties with a very ‘old’ and ‘early’ little circular dolmenitic tomb that I had visited up on Serre Pascale.

Now I’m not so sure. In fact, I’m confused. The dolmen 1 of Serre Pascale is tiny, and has ‘hallmark’ stones of varied colour. What I found was too wide to bear a capstone. So was that a neolithic ‘cabane’ that some archaeologist has cleared, or an elaborate hoax? It seems half-set in a tumulus of 8 metres, like a dolmen, but I can find no reference to it anywhere. Which means that I now have to go back up there to find Lauriol & Guilaine’s dolmen No. 4.

There are more photos of this ‘building’ on the Unknown Structure of les Lacs page.

_________________

The dolmens of les Lacs is turning out to be a much more complicated subject than I ever imagined. A more detailed explication with diagrams, (and poorly reproduced photos of the time) of the conflicting reports is to be found on the permanent Pages, to the right, under Lacs dolmens diagrams.

The situation on the next hillside to the west – Le Bouys – with five contested dolmens, is not going to be any easier to sort out. The situation at Bois-Bas, to the west again, is likely to be hellish: it’s a necropolis of 12 to 16 tombs . . .

When I first started exploring this whole area around Mailhac, and learnt that an oppidum was not a Roman fort but a Chalcolithic hill settlement, and that there was not just one but three necropoli, and that there existed a cave by a spring, and that there was a dolmen there too, and that the whole affair had been evolving and developing for a thousand years – I realised that getting all the information and photos and maps for the whole complex was going to stretch my abilities at ‘blorganisation’.

And so it proved : there are now posts and pages that don’t seem to come in any order, nor seem shaped in any cohesive way. I’m more of a reader than a librarian or a methodical historian. I’m hoping the tags will sort it all out, and that the grouping of all the topics under a ‘parent page’ will gather most of it together.

And consistent with this inconsistency, I shall now introduce the writer who introduced me to the whole subject of protohistory – who, fittingly was not an archaeologist at all, but an American and a poet : Gustaf Sobin. The book is ‘Luminous Debris. Reflecting on Vestige in Provence and Languedoc’. It was a propitious find in a Carcassonne second-hand bookshop. It is by turns dense, lively, academic, joyful – his chapter on Mailhacian pottery and its pictographs was exhilarating speculation and has inspired in me what I hope will be a life-long interest.

It sent me immediately to search the Internet – where I found references to the ‘vieux village ‘, and to the Grotte de Treille , and finally to the dolmen of Boun Marcou on a small hill called Trigodinnas, right next to Lou Cayla.

View from the chevet or headstone, to the foot.

For more on this go to Boun Marcou dolmen, Mailhac Page.

Les hauts lieux.

French is an impoverished language. Its dictionaries are a third smaller than ours, but it still manages to be poetic and expressive. So when I say I’ve just visited one of ‘les hauts lieux ‘ I don’t mean an arduous climb. I’ve just explored one of the great places in the south of France – massive, significant and important. But for all this it is still a low-lying, modest site with little to distinguish it from the landscape around.

The story is both extraordinary and humdrum. A fourteen-year-old girl, Odette Taffanel, begins to find things in her family’s vineyards in 1929. After the War, in 1948, she starts taking it seriously. In the 50’s she ropes in her younger brother Jean. Their work together unearths one of the biggest late bronze/early iron age sites in the Midi. Archaeologists flock to the site, and careers are made. She is awarded the Legion d’Honneur . The site and its findings are considered so significant that ‘Mailhacais’ becomes a benchmark for pottery and funerary rites in the Urn-Field culture of southern France. At 93, she is still writing and publishing – and still receiving visitors at her house in the village.

Photo of a grave emplacement – Necropolis Bassin 1

But the story of Lou Cayla goes back further than the Ancien Village – it starts with water from an abundant spring, a grotto, and a dolmen, all on the same small insignificant hill.

For more info and photos on all these aspects, see the Lou Cayla Parent Page.

In the XIII century, (some texts say the XII century) La Chapelle de Notre-Dame de Centeilles was built close to the site of a romanesque chapel, or of a Roman villa. Throughout the Middle Ages Centeilles was the centre of a thriving community on the trail between plain and mountain and was the focus of an important fair and market on 25th and 26th March. It was also a centre of pilgrimage for Ascension Day, with its Procession of the Rogations, and Assumption Day.

The first fresco to face the weary pilgrim was that of St. Christopher, patron saint of travellers.

La Révolution put an end to this tradition – the human population deserted it, and it was used as a barn. For the next one hundred years it was occupied by sheep. It was sold in 1960, for 500 francs. to the Diosese of Narbonne who later handed it over to Les Amis de Centailles, an association that undertook its repair and upkeep.

The early christian church had not chosen this place at random – it was a site of sacred significance since the earliest times. For wherever Our Lady has been installed and adored it is certain that she replaced a pre-christian animist or fertility cult – usually of Cybele, or Potnia Theron, the Queen of the Animals – one of the myriad names of the Mother Goddess.

For more photos and info- see the Chapelle de Centeilles Page

The information given on Quid for the Oppidum du Pic St-Martin is accurate – while the new IGN Seies Bleu map – and the http://www.geoportail.fr placing – is out by nearly 2 km. Its position is 2. 39′ 54″ E, 43. 20′ 11″ N and it is a most impressive structure. The site was occupied continuously from the Iron Age through to the arrival of the Visigoths. The earliest inhabitants were possibly the Ibères or the Ligures, but more certainly the Volques Tectosages [ a Celtic tribe that put up a fierce resistance to the invading Romans, and who were themselves an invading force from Middle Europe – the name translates best as Land-hungry Wolves ].

The scree slope rises about 300 feet from here to the walls.

More photos and info on the Pic St-Martin Hillfort Page

Quid is France’s Encyclopedia Britannica, on paper since 1967 and online since 1997. IGN is the Institute Géographique National – it began as an army mapping service in 1887 and went public in 1967. They are invaluable tools in researching old stones but they are not without weaknesses. This is what I found for Siran, a village nearby in the Minervois:

Cachette de fondeur de l’âge du Bronze à Centeilles. [Traces of Bronze Age smelting]

29 dolmens* et tumulus.

Habitat préhistorique à Centeilles, Ausine, Belvédère.

Champ des Morts.

Nécropole 1er âge du Fer à La Prade.

14 villas romaines, principalement : Najac, Saint-Michel de Montflaunez.

Oppidum du pic St-Martin occupé de l’âge du Fer au 6ème apr.J.-C.

Mosaïque gallo-romaine* à la chapelle de Centeilles.

Tombes wisigothiques à La Rouviole, Le Champ des Morts, Centeilles, Saint-Martin, Saint-Pierre des Troupeaux, Saint-Gontran.

And this is what the new IGN map says is there:

Centeilles seemed central to this rich and diverse little corner, and was one of the few from the list to be marked on the map, as was the Gallo-Roman fort [camp or oppidum] closeby. That confident red star looked a certain bet, so I set off this saturday to see what I could find – knowing that information on Quid could well be long out-of-date and that I could be beating around the bush all afternoon for nothing. But not suspecting that the map could get it so wrong.

The 13th.C. Chapelle de Notre-Dame-de-Centeilles was certainly there with its stone roof and holy well – as was a host of other fascinating structures and features [see following Posts & Pages] – and so were the remains of a massive emplacement deep in the wood where the map shows the red star. It wasn’t until I got home and compared this new map with the 1967 version that doubt set in about The Thing in the Wood. I now needed to persuade Jessi and Mary to come out on another hunt this sunday.

The story of this weekend’s two visits to Centeilles is complicated, so the photos about it all are over on the Pages section. Starting with the Not the Gallo-Roman Camp Page. And as fast as I can post them, the following will appear :-

The real Ancien Camp Gallo-Romain on the Pic St-Martin Hillfort Page.

The dolmen of Centeilles – or les Pierres Plantées, take your pick – on the Centeilles Dolmen Page.

The dolmen du Mourel des Fadas – on the Dolmen des Fadas Page.

The Chapelle de Notre-Dame de Centeilles – the extraordinary frescoes, its history, holy well and capitelles – on the Chapelle de Centeilles Page.

And the second earlier church at Centeilles [in many ways even more extraordinary] – on the Chapelle Ruinée Page. There was a third even earlier church here at one time – but it’s been lost . . .

And then there’s those Roman villas, and the visigoth necropoli, and the neolithic habitat here too, somewhere – but I need another visit or ten, for them.

This hunt could have gone disastrously wrong: with my enthusiastic daughter visiting from Ireland, and my unenthusiastic wife, I nearly managed to have us stumbling around the wrong mountain all afternoon. For, when doing anything involving maps and the wilds, it is generally advisable to know where you’re actually starting from . . .

Fortunately this time, despite starting from the wrong place and aiming at the wrong place, with Jessi’s unquenchable enthusiasm plus Mary’s unerring sense of direction plus a lot of luck, we got to the dolmens.

This is La Clape in the middle-distance : it’s occitan for a stoney hill. There are 8 dolmens scattered around this acre or two of limestone and box-shrub, according to Bruno Marc in his excellent ‘Guide to Dolmens & Menhirs of Languedoc-Roussillion’ – but we only found six.

How to get there plus lots more photos and text, on the La Clape Necropolis page, right column.